In a groundbreaking study, researchers have unearthed surprising connections between proto-cuneiform—the precursor to the world’s oldest writing system—and the designs left by engraved cylinder seals, a tool invented around 4400 BC. These intricate seals, rolled across clay to transfer motifs, exhibit striking similarities to proto-cuneiform symbols, suggesting a close relationship between early symbolic imagery and the subsequent development of written language. The study, led by Professor Silvia Ferrara, highlights how these seal designs were directly integrated into the proto-cuneiform script, offering a new perspective on how symbols transformed into standardized writing for record-keeping and communication in ancient Mesopotamia.

In a groundbreaking study, researchers have unearthed surprising connections between proto-cuneiform—the precursor to the world’s oldest writing system—and the designs left by engraved cylinder seals, a tool invented around 4400 BC. These intricate seals, rolled across clay to transfer motifs, exhibit striking similarities to proto-cuneiform symbols, suggesting a close relationship between early symbolic imagery and the subsequent development of written language. The study, led by Professor Silvia Ferrara, highlights how these seal designs were directly integrated into the proto-cuneiform script, offering a new perspective on how symbols transformed into standardized writing for record-keeping and communication in ancient Mesopotamia.

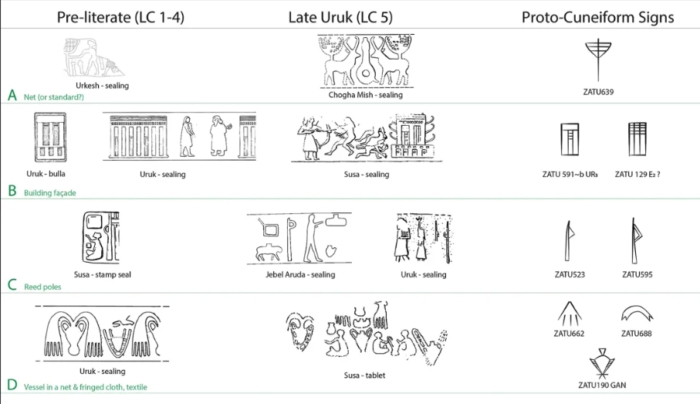

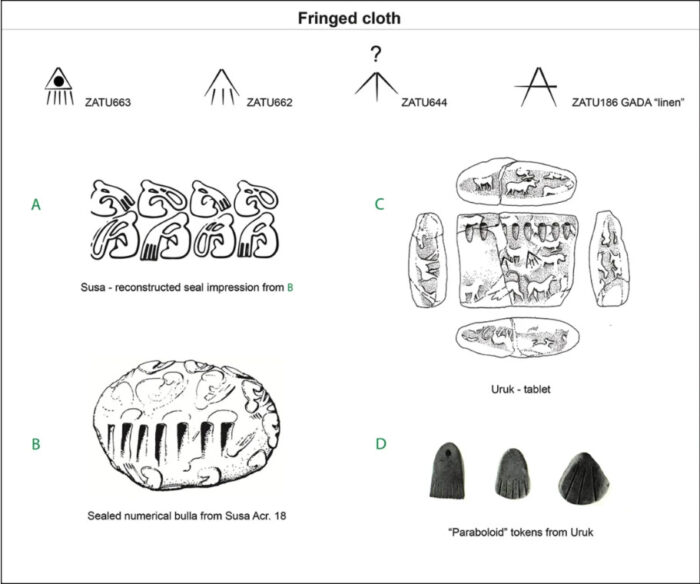

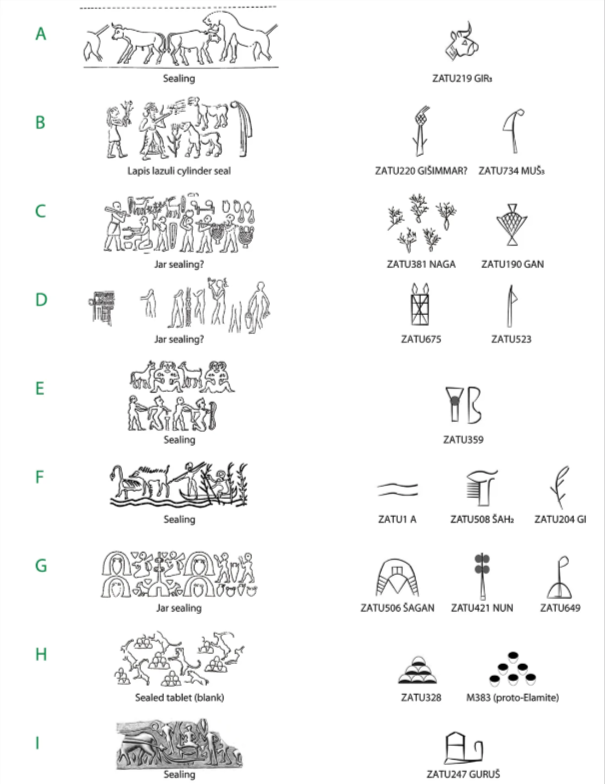

Proto-cuneiform emerged around 3350–3000 BC in the ancient city of Uruk, now in modern-day Iraq, where early urban societies sought ways to organize and document complex transactions. Uruk’s cylinder seals, with motifs depicting textiles, vessels, and other commodities, played a crucial role in this development. Scholars have long speculated on proto-cuneiform’s origins, particularly its non-numerical signs, which have remained enigmatic. This study illuminates how these seals, initially created for administrative purposes in a preliterate society, transitioned from decorative and functional items to elements of a formalized script used to document and verify trades, particularly within religious and economic institutions.

The implications of these findings are profound, suggesting that proto-cuneiform did not develop in isolation but was inspired by earlier visual forms that embodied symbolic meaning. Images on seals, such as textiles and jars, conveyed specific information in administrative contexts, and researchers noted that many proto-cuneiform signs closely resemble these seal motifs. Kathryn Kelley and Mattia Cartolano, co-authors of the study, emphasize that these motifs not only predate proto-cuneiform but also encapsulate the practical and economic concerns of early urban centers, shedding light on the motivations behind humanity’s earliest writing efforts.

Researchers hope to decode hundreds of proto-cuneiform symbols that remain a mystery in connecting seal imagery to proto-cuneiform. This study underscores how the transition from symbolic imagery to written language was more gradual and complex than previously believed. Dr. J. Cale Johnson of Freie Universität Berlin notes that this research fills a long-standing gap, providing concrete examples of how symbolic designs evolved into a true writing system. By linking proto-cuneiform with visual motifs on seals, this study reinforces the idea that the invention of writing was a transformative leap in human cognition, bridging prehistory and history.