Amelie von Wulffen at KW, Berlin

6 March to 17 May 2021

All Images courtesy of KW

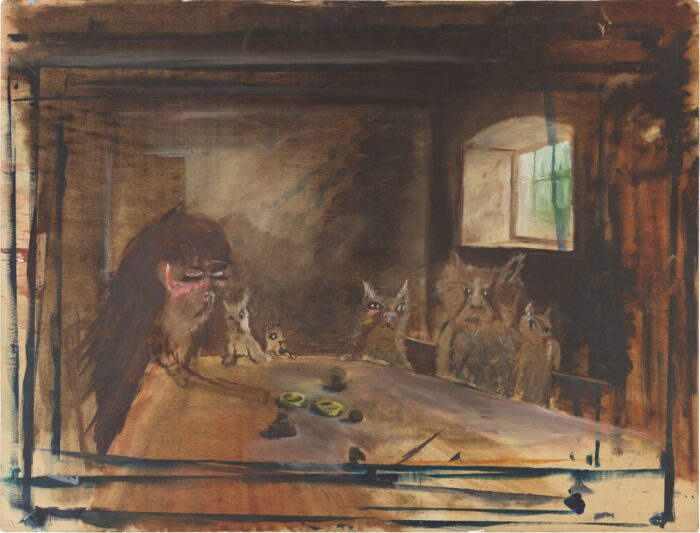

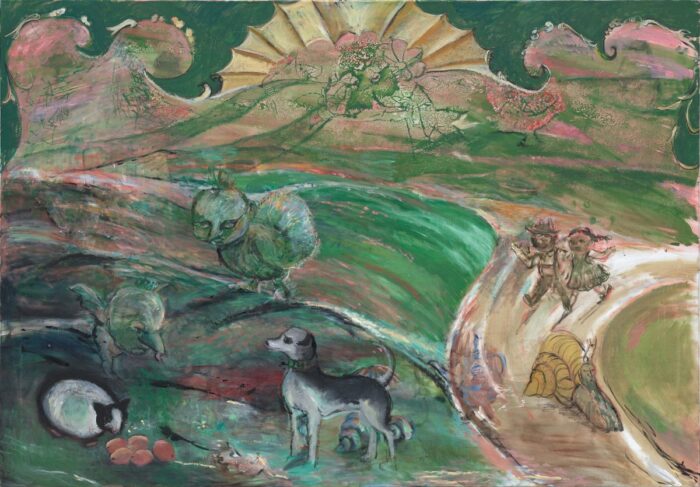

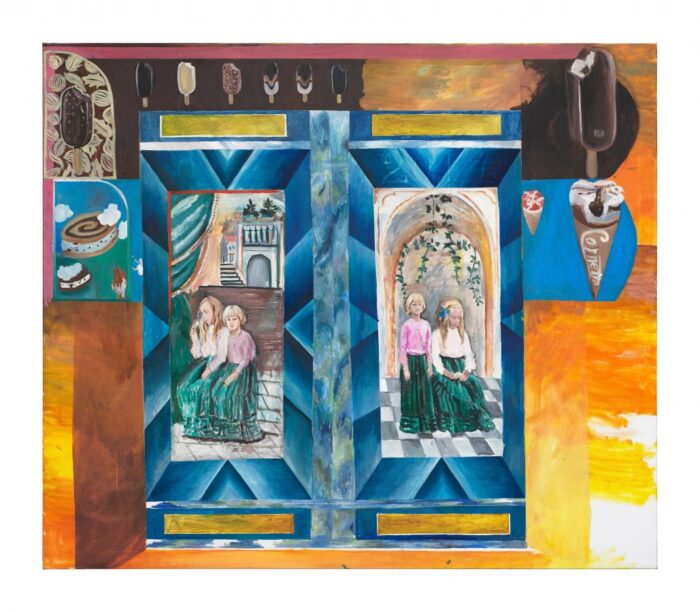

Berlin painter Amelie von Wulffen (*1966, DE) has forged an intricate, self-reflective body of work since the 1990s in which she is foregrounding the relationship of the inner and outer world as the frontline of a struggle between fears, guilt, and traumata on the one hand, and longings and repressed fantasies on the other, frequently set against the backdrop of her own family chronicle and German history. Von Wulffen’s often-melancholic paintings are imbued with a nervous, wistful air as if torn between self-mockery and hysteria. Yet, despite their gloomy undertone, they appear attentive to their viewers. They evoke unexpected and at times painful associations in which the position of the maker is opened up to question. Hybrid and mythical creatures conjured in fairy-tale-like landscapes act out dreamlike scenarios alongside historical figures. Elements from everyday life and art history are put on an equal footing as much as the clash of diverse painting styles and conflicting aesthetics is consciously sought.

Amelie von Wulffen’s exhibition at KW Institute for Contemporary Art—which marks the artist’s first institutional solo show in her hometown Berlin— presents a large number of new works alongside earlier ones in which Berlin is recurrently in the spotlight. This juxtaposition reveals interesting common threads and continuities and exposes central artistic concerns pervading her early oeuvre to newer ideas. The exhibition starts off with Die graue Partizipation (2001), a series of pencil drawings conjuring post-Wall Berlin life. By sketching the content of photographs that she had taken in clubs or at concerts the previous night, von Wulffen attempts to reappropriate these moments in her studio, stroke by stroke. Besides addressing subjective feelings of alienation from “others,” the drawings render palpable the disconnect of sight, thought, and sensation. What is seeing in relation to reality and personal experience, and where does that which is seen come to rest?

The adjacent room stages several self-portraits of von Wulffen, mostly from the series Bitte keine heiße Asche einfüllen (2009), showing the artist in various moods and with different attributes. This tentative play with forms of representation explores the constitution of one’s self and identity. The (un)ability to draw is here put to creative use and the potential of technical aids to self-perception, a photo, say, or a mirror, are thereby examined. How does the world (the self) end up in the picture the artist seems to ask.

Von Wulffen works habitually beyond the canvas, often by directly referencing the context of the exhibition venue in the work. Frequently furnishings serve as painting surfaces such as school chairs, a rustic cupboard, and handmade furniture. Painting

then represents a means to coalesce these otherwise disparate elements in a fictional space. Der verkannte Bimpfi (2016), a composite object made of a bed, a piano, and a confessional speaks to cultural and moral (self-)castigation, yet the way that it is adorned

with paintings subverts its message and turns it into a teenager’s den. Folksy landscape paintings and corny imitations of Impressionism collide here with starlets of ’70s American TV series and fictional psychodramas. The title refers to the eponymous classic of educational children’s literature, in which an anthropomorphic mushroom was used to school generations of German kids in aversion to prejudice, hate speech, guilt, and betrayal. A covert desire for rehabilitation shimmers through. Anthropomorphism stands for people’s need to see themselves reflected in all things and is a recurrent motif in von Wulffen’s oeuvre, as in her watercolor series This is how it happened (2011–2020)

for instance, whose emblematic portraits call to mind children’s books and advertizing graphics. Fruit, vegetables, screws, and paintbrushes live through banal or dramatic adventures, in which the innocent visual vocabulary clashes with everyday cruelty.

Since 2011, comics have been an additional means for von Wulffen to explore her own place in the (art) world, her market value as an artist, and issues of inclusion and exclusion. The situations that ensue—be it a place at the literally cool table at an art opening dinner, a drafty reminder of personal status and of wide-spread Amelie von Wulffen, Ohne Titel, 2018, oil on wood, Courtesy the artist and Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin careerist jockeying, or a sobering ego-downer in the form of falling popularity in a Googled artfacts ranking—are the subject of the slide show Am kühlen Tisch (2013). Fear of failure, frustration, loneliness, competition, and other existential questions are juggled

along with the highly superficial markers of the art scene, if only to refute its alleged relevance by pitting them against “real” crises in world history. The architectural collages from 1998 are based on photographs of modernist buildings, mostly located in East Berlin, among them the former Palast Hotel, the Czech Embassy, and the Western Bar on Alexander Platz. Von Wulffen transforms photographed reality, expanding its scope by painterly means in a way such as to lend it a far stronger physical presence. What ensues are hybrid spaces of photography and painting, which allow the artist to inquire into the specific potential afforded by painting—that which distinguishes it from photography. Also on show is the “claymation” film Pedigree (1996–1999, co-produced with Michael Graessner). Here, audio fragments from films by Michelangelo Antonioni and Andrei Tarkovsky provide the acoustic bed of politics and love in which a couple’s passionate encounter unfolds against a melodramatic technicolor sky.

Indexes and ordering systems have featured increasingly in von Wulffen’s work in recent years. A repainted antique rustic cupboard opens to reveal rows of ceramic gravestones, whose forms somewhat gruesomely mirror those in an ad for a popular German brand of popsicles featured elsewhere. Similarly uncanny formal links can be found in the photographs of children on the Christmas greetings cards incorporated into another of her paintings, or in the “menu” of Netflix’s films and series where so-called free choice is limited to Dexter or House of Cards, Nucki Nuss or Mini Milk. Von Wulffen wraps the seemingly self-evident logic of the “list” and of commensurability into ever more complex uses of mise-en-abyme: objects within objects and paintings within paintings open windows onto more and more layers of reality and thus call into question the

limitations of the image as well as its contribution in shaping reality.

For KW’s hall, Amelie von Wulffen has produced a new scenographic installation; a dramatic Wunderkammer that tackles the relationship between humans and nature, which is still mainly defined by romantic notions of landscape and scenery, even in the face of total environmental collapse. On the painted plinths, the artist raises an army of anthropomorphic object collages which, like Wutbürger (outraged citizens), confront the viewers with accusatory stares. These endearingly crafted monstrosities could well have been washed ashore. Their tiny bodies made of seashells, wood, and moss belong possibly in an ethnological museum—or are they perhaps a crossbreed of tacky souvenir art, trinkets, or Meissen porcelain figurines? They personify the clamor of a dying world that is no longer available for vacation, recreation, or daydreamed routes out of our daily routine. The wooden plinths painted with seascapes can be read not only as maritime pittoresques but also as apocalyptic visions: the murky water in the space is already knee-deep. Storm-driven, washed-out light, flotsam, and oil fields conjure the palpable

consequences of environmental pollution and war. In their midst, one can see a painted old man who appears to be on his dying bed. A small figure made of seashells is perched on his chest. Will it accompany him to the grave as a funerary offering? At this point,

the scenery shifts and we find ourselves in a pharaoh’s tomb. Accompanying the group, an excrement figure made of papier-mâché is leaning warily against a tree trunk. A swarm of sea mussel and papier mâché bluebottle mutations herald ecological disaster, and the

walls all around are partly smeared with brown. Naked but for a purse, the excrement figure, which may well epitomize the artist, appears to be offering the small artifacts for sale, as on a flea market. The figure is not least a reference to the comic Die Findlinge

(The Boulders) (2017), in which von Wulffen reflected on the rusticity of German painting and its tedious preference for brown. As in many of her works, German history features here as a heavy legacy.

Other new paintings hung around the installationaddress once again the abysmal depths of family,where leaden problems and all things repressed are handed down along with love and culture. Particularly emotional, they speak to a final farewell to the parents.

The retreat into a logic forged by dreams characterizes these works, in which resurgent memories of infantile cruelty, vain attempts for atonement, and hopes to end the vicious circle of guilt mingle with the question as to whether human beings are, after all, wholly

incompatible with their environment.

On the occasion of the solo exhibition at KW, Amelie von Wulffen has produced a limited edition of mutant bluebottles made of sea mussels and papier mâché, referencing the installation in the hall. Accompanying the show, von Wulffen’s collected comics from 2011 to 2020 are published with Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther und Franz König.

why is somebody else always the bad guy ?

We artists wd. never dream of doing RONG things