Abraham Cruzvillegas: La Señora de Las Nueces at Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris

January 23 – February 27th, 2021

All images courtesy of Galerie Chantal Crousel

Galerie Chantal Crousel is pleased to host the fifth Abraham Cruzvillegas solo exhibition, La Señora de Las Nueces, in which the artist presents a set of sculptures, a series of monoprints and a video. The works are the result of a long term reflection about the material and cultural history of the Señor de las Limas, also known as Las Limas Monument 1, a sculpture dating back to 900-400 BCE, emblematic of Olmec culture*. Found in 1965 by two children from Las Limas village looking for a stone with which to crack a nut from a palm, the sculpture represents a person sitting cross-legged with the loose body of a were-jaguar baby laying over his arms**. Their skin is incised with symbolic motifs that archeologists attribute to the main divinities of the Olmec pantheon and to the power insignia of several meso-American cultures (rectangle with a cross in the middle). The back of the sculpture is flat, at the lower half of which are two symmetrical holes which seem designed for passing a rope through to facilitate its transport.

The uncertainty in the hypotheses put forward as to the usage and symbolism of the Señor de Las Limas, as well as the conditions of its discovery and the veneration it inspired prior to inclusion in the Xalapa museum of anthropology’s collection are a starting-point for understanding the works of Abraham Cruzvillegas shown here. Entitled La Señora de Las Nueces, a video in the exhibition shows the close-up of a woman’s hand —archeologist Patricia Carot, specialist in pre-Columbian Purepecha culture— using two stones to break a nut, then peeling it. The almost instinctive familiarity of gestures allowing the fruit to be opened is like a replay of the original discovery of the Olmec sculpture in the 1960s. Recorded by the artist, the short clip of the archeologist’s hand in action focuses the viewer’s attention on her movements. And while Cruzvillegas is intrigued by Patricia Carot’s reproduction of ancestral gestures, he is equally fascinated by the dialogue between body, stone and fruit.

Attention to movement is central to Cruzvillegas’ process of creating the hanging sculptures in the main gallery. Made from urban objets trouvés and materials picked up around the city (odd bits of furniture, wooden boards and planks, metal strips, strings, stones, computer keyboard…), they are all put together to be carried and carry something else. Their architecture includes a platform or a basket, a back, and straps. Based on scientific proposals as to the transportation techniques the Olmecs used for the Señor de Las Limas and its symbolic function, Abraham Cruzvillegas completes his sculptures by a hybrid activity: strapped to his body, he embarks each one on a journey between the gallery and a place of personal importance in this day-to-day life (The École des Beaux-Arts where he teaches and his home, amongst others). Brought back to the gallery, they signify the end of a series of performances in which the artist attended to his serendipitous encounters with the fragments picked out of the urban fabric. Creating the sculptures in part expresses a quest to understand the body as tool. Handling and moving them is akin to physically experiencing the reproduction of routine gestures. The question of the relation between the body and the work of art is fundamental to Abraham Cruzvillegas’ thinking. In the present exhibition, he examines the notion of labor, understood figuratively as a “continuous process of transformation”*** of both the body and the œuvre. The task is to trigger an encounter between two living things (the human body and matter) and observe the resulting mutual metamorphoses: how do the body and sculptures interact in the wanderings in town? How do they ply a bodily attitude or position when carried or handled?

We then see carrying as choreography and repertory, an extension of the performative exercise begun with Autoreconstrucción: To Insist, to Insist, to Insist****, a performance where professional dancers activated Cruzvillegas’ hanging sculptures in a spectacular play.

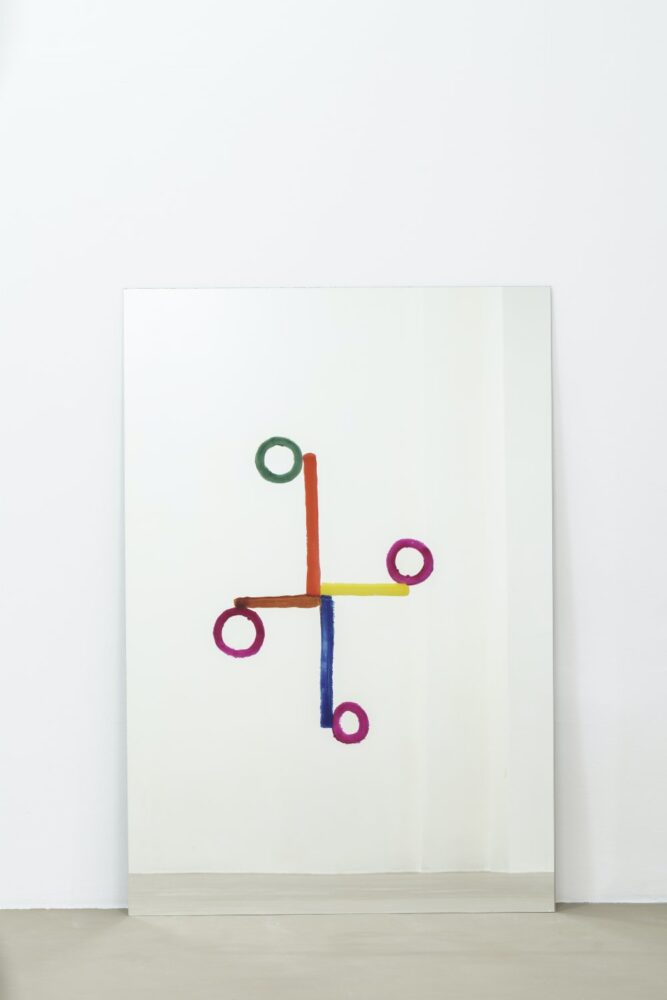

Made in the weeks leading up to the exhibition’s opening, the monoprints attached to the gallery walls consist in colorful abstract motifs. Made on a mirror, each drawings is transferred onto paper, then attached by means of beer capsules onto a plain wooden frame, with no protective glass. The capsules are thus used as ligatures between the materials representing the sculptures mentioned earlier. In this series of works on paper entitled On the road of La Señora de Las Nueces, the body is involved once again not just by the printing technique, by its physicality, but also by the reflection of himself in the mirror, now transfigured into medium. For Cruzvillegas, the painted shapes of the monoprints represent a sort of projection of the sculptures prior to their creation. The straight and oblique lines reflect the angular geometry of each sculpture’s basic parts, while the curves reiterate the straps and handles allowing the artist to carry them on his back. Neither sketches not drafts, the repetitive nature of the prints also echoes the artist’s meditative urban footsteps.

__

* The Olmec were a multiethnic, pre-Columbian people established on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, in the Valley of Mexico and along the Pacific coastline down to present-day Salvador. Their presence in the region ranged from 2500 to 500 BCE and was revealed in the mid-19th century by the discovery of a colossal head, sculpted from basalt, on the now archeological site of Tres Zapotes in the state of Veracruz.

** Hybrid figures are part of the sculptural repertory of Olmec art, the werejaguar is a recurrent example of which. It belongs to a religious art form and imagery that researchers interpret as describing the relations between man and animal.

*** Definition: CNRTL.

****First performed in Mexico, then at The Kitchen (New York), in collaboration with choreographer Bárbara Foulkes and Andrès García Nestitla and revived at the inauguration of the Art Basel Miami Beach Grand Ballroom in December the same year.

Abraham Cruzvillegas wishes to thank Gilbert Brownstone and Samantha Barroero for allowing him to work at Brownstone Fondation on the construction of some elements of this project; as well as Alberto Cabrera Luna, and Gabriel Moraes Aquino for accompanying and documenting the process of this project.